This Blog is Created by Cyd M.Batalon and Ana Mae Cabahug

Medieval Times

The Middle Ages (adjectival forms: medieval, mediaeval, and mediæval) is the period of European history encompassing the 5th to the 15th centuries, normally marked from the collapse of the Western Roman Empire (the end of Classical Antiquity) until the beginning of the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery, the periods which ushered in the Modern Era. The medieval period thus is the mid-time of the traditional division of Western history into Classical, Medieval, and Modern periods; moreover, the Middle Ages usually is divided into the Early Middle Ages, the High Middle Ages, and the Late Middle Ages.

In the Early Middle Ages, depopulation, deurbanization, and barbarian invasions, which began in Late Antiquity, continued apace. The barbarian invaders formed new kingdoms in the remains of the Western Roman Empire. In the 7th century North Africa and the Middle East, once part of the Eastern Roman Empire, became an Islamic Empire after conquest by Muhammad's successors. Although there were substantial changes in society and political structures, the break with Antiquity was not complete. The Eastern Roman Empire – or Byzantine Empire – survived and remained a major power. Additionally, most of the new kingdoms incorporated many of the extant Roman institutions, while monasteries were founded as Christianity expanded in western Europe. In the 7th and 8th centuries, the Franks, under the Carolingian dynasty, established an empire covering much of western Europe; the Carolingian Empire endured until the 9th century, when it succumbed to the pressures of invasion — the Vikings from the north; the Magyars from the east, and the Saracens from the south.

During the High Middle Ages, which began after AD 1000, the population of Europe increased greatly as technological and agricultural innovations allowed trade to flourish and crop yields to increase. Manorialism — the organization of peasants into villages that owed rent and labor services to the nobles; and feudalism — the political structure whereby knights and lower-status nobles owed military service to their overlords, in return for the right to rent from lands and manors - were two of the ways society was organized in the High Middle Ages. Kingdoms became more centralized after the breakup of the Carolingian Empire. The Crusades, first preached in 1095, were military attempts, by western European Christians, to regain control of the Middle Eastern Holy Land from the Muslims, and succeeded long enough to establish Christian states in the Near East. Intellectual life was marked byscholasticism and the founding of universities; and the building of Gothic cathedrals, which was one of the outstanding artistic achievements of the High Middle Ages.

The Late Middle Ages were marked by difficulties and calamities, such as famine, plague, and war, which much diminished the population of western Europe; in the four years from 1347 through 1350, the Black Death killed approximately a third of the European population. Controversy, heresy, and schism within the Church paralleled the warfare between states, the civil war, and peasant revolts occurring in the kingdoms. Cultural and technological developments transformed European society, concluding the Late Middle Age and beginning the Early Modern period.

Later Roman Empire

The Roman Empire reached its greatest territorial extent during the 2nd century AD, with the following two centuries witnessing the slow decline of Roman control over its outlying territories.[15] Economic issues, including inflation, and external pressures on the frontiers combined to make the 3rd century politically unstable, with a number of emperors coming to the throne only to be rapidly replaced by new usurpers.[16] Military expenses increased steadily during the 3rd century, mainly in response to the need to defend against the renewed war with Sassanid Persia, which began in the middle of the 3rd century.[17] The army doubled in size and various reforms in composition resulted in a new emphasis on cavalry and smaller units instead of the legion as the main tactical unit.[18] The need for revenue led to increased taxes and a decline in numbers of the curiallandowning class, and decreasing numbers of them willing to shoulder the burdens of holding office in their native towns.[17] More bureaucrats were needed in the central administration to deal with the needs of the army, which led to complaints from civilians that there were more tax-collectors in the empire than tax-payers.[18]

The Emperor Diocletian (r. 284–305) split the empire into separately administered eastern and western halves in 286; however, the empire was not considered divided by its inhabitants or rulers, as legal and administrative promulgations in one division were considered valid in the other.[19][c] In 330, after a period of civil war, Constantine the Great (r. 306–337) refounded the city of Byzantium as the newly renamed eastern capital, Constantinople.[20] Diocletian's reforms created a strong governmental bureaucracy, reformed taxation, and strengthened the army, which bought the empire time but did not completely resolve the problems it was facing: excessive taxation, a declining birthrate, and pressures on its frontiers amongst others.[21] Civil war between rival emperors became common in the middle of the 4th century, diverting men from the empire's frontier forces and allowing the barbarians to encroach.[22] But for much of the 4th century, Roman society had reached a new, stable form that differed from the earlier classical period in a number of significant ways - a widening gulf between the rich and poor as well as a decline in the vitality of the smaller towns.[23] Another change was the conversion of the empire to Christianity, which occurred in a gradual process that lasted from the 2nd through the 5th centuries.[24][25]

In 376, the Ostrogoths, fleeing from the Huns, received permission from the Roman emperor Valens (r. 364–378) to settle in the Roman province of Thracia. The settlement did not go smoothly, and when Roman officials mishandled the situation, the Ostrogoths began to raid and plunder Thracia. Valens, attempting to put down the disorder, was killed in battle with the Ostrogoths at the Battle of Adrianople on 9 August 378.[26] Besides the barbarian threat from the north, internal divisions within the empire, especially within the Christian Church, caused troubles.[27] In 400, the Visigoths invaded the Western Roman Empire and, although briefly forced back from Italy, in 410 they were able to sack the city of Rome.[28] While the Visigoths were invading, in 406 the Alans, Vandals, and Suevi crossed into Gaul; over the next three years they spread across Gaul and in 409 crossed the Pyrenees Mountains into modern-day Spain.[29] Other groups of barbarians took part in the movements of peoples in this time period. The Franks, Alemanni, and the Burgundians eventually all ended up in northern Gaul while the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes settled in Britain.[30] In the 430s the Huns began invading the empire; their king Attila led invasions into the Balkans in 442 and 447, into Gaul in 451, and into Italy in 452.[31] With Attila's death in 453, the Hunnic confederation he led fell apart.[32] All of these invasions by the varied tribes totally rearranged the political and demographic face of what had been the Western Roman Empire.[30]

By the end of the 5th century the western section of the empire was divided into smaller political units, ruled by the tribes that had invaded in the early part of the century.[33] The last emperor of the west, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed in 476, which has led that year to be traditionally cited as the end of the Western Roman Empire.[8][d] The Eastern Roman Empire, conventionally referred to as the "Byzantine Empire" after the fall of its western counterpart, had little ability to assert control over the lost western territories. Even though Byzantine emperors maintained a claim over the territory, and no barbarian king in the west dared to elevate himself to the position of Emperor of the West, Byzantine control of most of the West could not be sustained; the reconquest of the Italian peninsula and Mediterranean periphery by Justinian was the sole, and temporary, exception.[34]

New Societies

Although the political structure in western Europe had changed, the divide is not as extensive as some historians have claimed. Although usually described as "invasions", they were not always just military expeditions but were mostly caused by the movement of peoples immigrating into the Empire. Such movements were aided by the refusal of the western Roman elites to either support the army or pay the taxes that would have allowed the military to suppress the migration.[35] The emperors of the 5th century were often controlled by military strongmen such as Stilicho (d. 408), Ricimer (d. 472), Gundobad (d. 516), or Aspar (d. 471), and when the western emperors ceased, many of the kings who replaced them were from the same background as those military strongmen. Intermarriage between the new kings and the Roman elites was common.[36] This led to a fusion of the Roman culture with the customs of the invading tribes, including the popular assemblies which allowed free male tribal members more say in political matters.[37] Material artifacts left by the Romans and the invaders are often similar, with tribal items often being obviously modeled on Roman objects.[38] Similarly, much of the intellectual culture of the new kingdoms was directly based on Roman intellectual traditions.[39] An important difference was the gradual loss of tax revenue by the new polities. Many of the new political entities no longer provided their armies with tax revenues, instead allocating land or rents. This meant there was less need for large tax revenues and so the taxation systems decayed.[40] Warfare was common between and within the kingdoms. Slavery declined as the supply declined, and society became more rural.[41]

Between the 5th and 8th centuries, new peoples and powerful individuals filled the political void left by Roman centralized government.[39] The Ostrogoths settled in Italy in the late 5th century under Theodoric (d. 526) and set up a kingdom marked by its cooperation between the Italians and the Ostrogoths, at least until the last years of Theodoric's reign.[42] The Burgundians settled in Gaul, and after an earlier kingdom was destroyed by the Huns in 436, formed a new kingdom in the 440s between today's Geneva and Lyon. This grew to be a powerful kingdom in the late 5th and early 6th centuries.[43] In northern Gaul, the Franks and Britons set up small kingdoms. The Frankish kingdom was centered in northeastern Gaul and the first king of whom much is known is Childeric, who died in 481.[e] Under Childeric's son Clovis (r. 509–511), the Frankish kingdom expanded and converted to Christianity. The Britons, related to the natives of Britannia, settled in what is now Brittany, which took its name from their settlement.[45] Other kingdoms were established by the Visigoths in Spain, the Suevi in northwestern Spain, and the Vandals in North Africa.[43] In the 6th century, the Lombards settled in northern Italy, replacing the Ostrogothic kingdom with a grouping of duchies that occasionally selected a king to rule over all of them. By the late 6th century this arrangement had been replaced by a permanent monarchy.[46]

With the invasions came new ethnic groups into parts of Europe, but the settlement was uneven, with some regions such as Spain having a larger settlement of new peoples than other places. Gaul's settlement was uneven, with the barbarians settling much thicker in the northeast than in the southwest. Slavonic peoples settled in central and eastern Europe and into the Balkan Peninsula. The settlement of peoples was accompanied by changes in languages. The Latin of the Western Roman Empire was gradually replaced by languages based on Latin but distinct. These changes from Latin to the new languages like French or Portuguese or Romanian took many centuries, however, and went through a number of stages. Greek remained the language of the Byzantine Empire, but the migrations of the Slavs added Slavonic languages to the mix.[47]

Trade and economy

The barbarian invasions of the 4th and 5th centuries caused disruption in trade networks around the Mediterranean. African trade goods disappear from the archeological record slowly, first disappearing from the interior of Europe and by the 7th century they are usually only found in a few cities such as Rome or Naples. By the end of the 7th century, under the impact of the Muslim conquests, African products are no longer found in Western Europe, and have been mostly replaced by local products. The replacement of trade goods with local products was a trend throughout the old Roman lands that happened in the Early Middle Ages. This was especially marked in the lands that did not lie on the Mediterranean, such as northern Gaul or Britain. What non-local goods that appear in the archeological record are usually luxury goods. In the northern parts of Europe, not only were the trade networks local, but those goods that were produced were simple, with little use of pottery or other complex products. Around the Mediterranean Sea, however, pottery remained prevalent and appears to have been traded over medium range networks and not just produced locally.[67]

Church and monasticism

Main article: History of the East–West Schism

Christianity was a major unifying factor between Eastern and western Europe before the Arab conquests, but the conquest of North Africa sundered maritime connections between the areas. Increasingly the Byzantine Church, which became theOrthodox Church, differed in language, practices, and liturgy from the western Church, which became the Catholic Church. The eastern church used Greek instead of the western Latin. Theological and political differences emerged, and by the early and middle 8th century issues such as iconoclasm, clerical marriage, and state control of the church had widened enough that the cultural and religious differences were greater than the similarities.[68] The formal break came in 1054, when the papacy and the patriarchy of Constantinople clashed over papal supremacy and mutually excommunicated each other, which led to the division of Christianity into two churches – the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church.[69]

The ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Empire survived the barbarian invasions in the west mostly intact, but the papacy was little regarded, with few of the western bishops looking to the bishop of Rome for religious or political leadership. Many of the popes prior to 750 were in any case more concerned with Byzantine affairs and eastern theological concerns. The register, or archived copies of the letters, of Pope Gregory the Great, (pope 590–604) survives, and of those more than 850 letters, the vast majority were concerned with affairs in Italy or Constantinople. The only part of western Europe where the papacy had influence was Britain, where Gregory had sent the Gregorian mission in 597 to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity.[70] Other missionary efforts were led by the Irish, who between the 5th and the 7th centuries were the most active missionaries in western Europe, with missionaries going first to England and Scotland and then later onto the continent. Irish missionaries, under such monks as Columba (d. 597) and Columbanus (d. 615), not only founded monasteries but also taught in Latin and Greek and were active authors of secular and religious works.[71]

The Early Middle Ages witnessed the rise of monasticism in the West. The shape of European monasticism was determined by traditions and ideas that originated in the deserts of Egypt and Syria. The style of monasticism that focuses on community experience of the spiritual life, called cenobitism, was pioneered by Pachomius (d. 348) in the 4th century. Monastic ideals spread from Egypt to western Europe in the 5th and 6th centuries through hagiographical literature such as theLife of Anthony.[72] Benedict of Nursia (d. 547) wrote the Benedictine Rule for Western monasticism during the 6th century, detailing the administrative and spiritual responsibilities of a community of monks led by an abbot.[73] Monks and monasteries had a deep effect on the religious and political life of the Early Middle Ages, in various cases acting as land trusts for powerful families, centres of propaganda and royal support in newly conquered regions, bases for mission, and proselytization.[74] In addition, they were the main and sometimes only outposts of education and literacy in a region. Many of the surviving manuscripts of the Roman classics were copied in monasteries in the early Middle Ages.[75] Monks were also the authors of new works, including history, theology, and other subjects, which were written by authors such as Bede (d. 735), a native of northern England who wrote in the late 7th and early 8th century.[76]

Art and architecture

Main articles: Medieval art and Medieval architecture

Further information: Migration Period art and Pre-Romanesque art and architecture

Few truly large stone buildings were attempted between the Constantinian basilicas of the 4th century and the 8th century, but many smaller stone buildings were built during the 6th and 7th centuries. By the beginning of the 8th century, the Carolingian Empire revived the basilica form of architecture.[107] One feature of the renewed basilica was the use of a transept,[108] or the "arms" of a cross-shaped building that are perpendicular to the long nave.[109] Other new features of religious architecture include the crossing tower[110] and a monumental entrance to the church, usually at the west end of the building.[111]

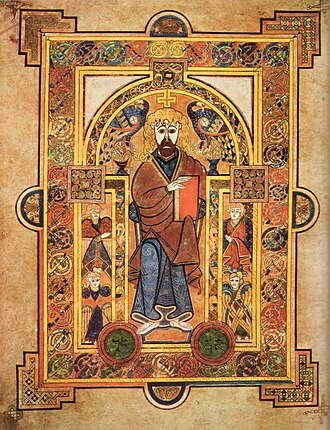

Carolingian art was produced for a small group of figures around the court, and the monasteries and churches they supported. It was dominated by efforts to regain the dignity and classicism of imperial Roman and Byzantine art, but was also influenced by the Insular art of the British Isles. Insular art integrated the energy of Irish Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Germanic styles of ornament with Mediterranean forms such as the book and established many characteristics of art for the rest of the medieval period. Surviving religious works from the Early Middle Ages are mostly illuminated manuscripts and carved ivories, originally made for metalwork that has been destroyed for its materials.[112][113] Objects in precious metals were the most prestigious form of art, but nearly all are lost, except for a few crosses like the Cross of Lothair, several reliquaries, and finds such as the Anglo-Saxon burial at Sutton Hoo and the hoards of Gourdon from Merovingian France, Guarrazar from Visigothic Spain and Nagyszentmiklós near Byzantine territory. There are numbers of survivals from the large brooches in fibula or penannular form that were a key piece of personal adornment for elites, including the Irish Tara Brooch.[114] Highly decorated books were mostly Gospel books and these have survived in larger numbers, including the Insular Book of Kells and Book of Lindisfarne, and the imperial Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, which is one of the few to retain its "treasure binding" of gold encrusted with jewels.[115] Charlemagne's court seems to have been responsible for the crucial acceptance of figurative monumental sculpture in Christian art,[116] and by the end of the period near life-size figures such as the Gero Cross were common in important churches.[117]

Military and technological developments

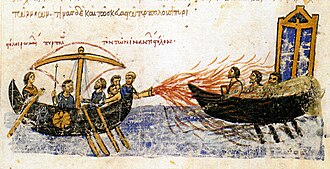

During the later Roman Empire, the principal military developments had to do with attempts to create an effective cavalry force as well as the continued development of highly specialized types of troops. The creation of cataphract-type soldiers was an important feature of the 5th century. The various invading tribes had differing emphasis on types of soldiers - ranging from the primarily infantry Anglo-Saxon invaders of Britain to the Vandals and Visigoths which had a high percentage of cavalry in their armies.[118] During the early invasion period, the stirrup had not been introduced into warfare, which limited the usefulness of cavalry as shock troops, but not to the extent that has generally been proclaimed. It was still possible for cavalry to use shock tactics in battle, especially when the saddle was built up in front and back to allow greater support to the rider.[119] The greatest changes in military affairs during the invasion was the adoption of the Hunnic composite bow in place of the earlier, and weaker, Scythiancomposite bow.[120] Another development of the invasion period was the increasing use of longswords[121] and the decrease in the use of scale armour and the increasing use of mail amour and lamellar armour.[122]

During the early Carolingian period, a decline in the importance of infantry and light cavalry began, with a corresponding dominance of military events by the elite. The use of militia-type levies of the free population declined over the Carolingian period.[123] Although much of the Carolingian armies were mounted, a large proportion during the early period appear to have been mounted infantry, rather than true cavalry.[124] One exception was Anglo-Saxon England, where the armies were still composed of local levies, known as the fyrd, which were led by the local elites.[125] In military technology, one of the main change was the return of the crossbow, which had previously been known in Roman times, but reappeared as a military weapon during the last part of the Early Middle Ages.[126] Another great change was the introduction of the stirrup, which allowed the more effective use of cavalry as shock troops. One final technological change that had implications beyond the military was the horseshoe, which allowed horses to be used in rocky terrain.[127]

Crusades

Main articles: Crusades, Reconquista, and Northern Crusades

In the 11th century, the Seljuk Turks took over much of the Middle East, taking the ancient lands of Persia during the 1040s, Armenia in the 1060s, and capturing Jerusalem in 1070. In 1071, the Turkish army defeated the Byzantine army at the Battle of Manzikert and captured the Byzantine Emperor Romanus IV (r. 1068–1071). This allowed the Turks to invade Asia Minor, which dealt a dangerous blow to the Byzantine Empire by seizing a large part of the empire's population and its economic heartland. Although the Byzantines managed to regroup and recover somewhat, they never regained Asia Minor and were often on the defensive. The Turks also ran into difficulties, losing control of Jerusalem to the Fatimids of Egypt and suffering from a series of internal civil wars.[158]

The Crusades intended to seize Jerusalem from Muslim control. The first Crusade was preached by Pope Urban II (pope 1088–1099) at the Council of Clermont in 1095 in response to a request from the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081–1118) for aid against further Muslim advances. Urban promised indulgence to anyone who took part. Tens of thousands of people from all levels of society mobilized across Europe, and captured Jerusalem in 1099 during the First Crusade. The Crusaders consolidated their conquests in a number of Crusader states. During the 12th century and 13th century, there were a series of conflicts between them and the surrounding Islamic states. Further crusades were called to aid the Crusaders,[159] or to try to regain Jerusalem, which was captured by Saladin in 1187.[160] Military religious orders such as the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller were formed and went on to play an integral role in the Crusader states.[161] In 1203, the Fourth Crusade was diverted from the Holy Land to Constantinople, and captured that city in 1204, setting up a Latin Empire of Constantinople[162] and greatly weakening the Byzantine Empire, which finally recaptured Constantinople in 1261, but the Byzantines never regained their former strength.[163] By 1291 all the Crusader states had been either captured or forced from the mainland, with a titular Kingdom of Jerusalem surviving on the island of Cyprus for a number of years after 1291.[164]

Popes called for crusades to take place other than in the Holy Land, with crusades being proclaimed in Spain, southern France, and along the Baltic.[159] The Spanish crusades became fused with the Reconquista, or reconquest, of Spain from the Muslims. Although the Templars and Hospitallers took part in the Spanish crusades, Spanish military religious orders were also founded in imitation of the Templars and Hospitallers, with most of them becoming part of the two main orders of Calatrava and Santiago by the beginning of the 12th century.[165] Northern Europe also remained outside Christian influence until the 11th century or later; these areas also became crusading venues as part of the Northern Crusades of the 12th through the 14th centuries. This too spawned a military order, the Order of the Sword Brothers. Another order, the Teutonic Knights, although originally founded in the Crusader states, focused much of its activity in the Baltic after 1225, and in 1309 moved its headquarters to Marienburg in Prussia.[166]

Walang komento:

Mag-post ng isang Komento